I kept trying to make this into two essays, one about coming-of-age stories and one about quests, and I kept not being able to write either one of them.

And then, driving to a class I’m taking for my day job, singing R.E.M. songs (as one does), I suddenly remembered that a coming-of-age story is a quest, and a quest, as Joseph Campbell tells us, is a coming-of-age story. On the level of symbols and archetypes and fairytale forests, they’re the same thing. Writing about them separately was never going to work.

A coming-of-age story—a bildungsroman to use the fancy technical term—is the narrative of how its protagonist makes the transition from child to adult. If you think of it as a quest, the grail is self-knowledge, that being the part of adulthood that doesn’t come simply with the passage of time. Bildungsromans are often about teenagers, but they need not be. In modern Western society, which both lacks a definitive coming-of-age rite and provides the luxury of extending childhood well past physical maturity, people may still be trying to figure out who they are in their twenties, or even thirties.

Therefore, stories about reaching adulthood need not be of interest only to teenagers, either. The Harry Potter books are a bildungsroman that have been avidly devoured by millions of adults. Buffy the Vampire Slayer didn’t run for seven seasons because Buffy’s bildungsroman was of interest only to teenagers. Ursula K. Le Guin says in an essay about A Wizard of Earthsea (itself an excellent bildungsroman), “I believe that maturity is not an outgrowing, but a growing up: that an adult is not a dead child, but a child who survived.” Even when we have completed our own bildungsromans, we are still drawn to the story of how a child survives the quest for self-knowledge.

What makes a story a story is that something changes. Internal, external, small or large, trivial or of earth-shattering importance. Doesn’t matter. The change is what the story pivots on, what makes it more than an anecdote or vignette or the rambling, endless, soul-crushingly tedious reminiscences of the drunk guy who corners you at a party. A quest is a story that can have either internal change, external change, or both, since it is literally a journey undertaken to achieve a particularly difficult goal, but both journey and goal may be metaphorical rather than literal, and the whole thing can be charged with symbolism. Tolkien is a splendid example and also one that overshadows pretty much every secondary-world fantasy to come after; the quest to throw the One Ring into Mount Doom is literal, metaphorical, and symbolic, all at once. There are perils and obstacles, companions come and go, the quest is successful, or fails (or both, as Frodo fails, but Gollum inadvertently succeeds), or the protagonist discovers, at the last possible moment, some very good reason why it shouldn’t be completed. Regardless, the journey has resulted in change and thus has created a story.

I don’t agree with Joseph Campbell on all points, but he does provide a useful explanation of why the quest and the bildungsroman are linked to each other. Essentially, he says the quest, the “Hero’s Journey,” is an externalization of the inward passage from childhood to adulthood, the bildungsroman. The Hero starts his journey as a boy and ends it as a man. (The original Star Wars trilogy is a classic example: think of Whiny Luke at the beginning and Jedi Luke at the end.) Campbell’s Hero is, of course, quite obviously default-male, and that is a problem with his model.

It’s certainly not true that women can’t be the protagonists of bildungsromans, both in fantasy and out: Charlotte Brontë, Louisa May Alcott, Laura Ingalls Wilder, L. M. Montgomery, Madeleine L’Engle, Anne McCaffrey (the Harper Hall trilogy), Diana Wynne Jones, Mercedes Lackey, Tamora Pierce, Caroline Stevermer, Robin McKinley, Terry Pratchett (Tiffany Aching), Kate Elliott—and the list only grows longer. And there’s equally no reason that women can’t go on quests—but it’s harder to imagine, just as it’s hard to imagine fantasy without quests, because the ingrained model for women’s bildungsromans (as Brontë, Alcott, Wilder, and Montgomery all demonstrate) is that adulthood and identity mean marriage (decidedly not the case in men’s bildungsromans). That in turn implies, if not outright requires, a story arc tending towards domestic stability rather than heroic (or “heroic,” if you prefer) wandering. Even when you reject that model, that means your own quest, to reverse tenor and vehicle for a moment, has to plunge off the path into the wilderness, especially if you want to go farther than simply undercutting the trope, as Bronte does in her excellent last novel, Villette.

And there are female protagonists in fantasy who quest. Mary Brown’s The Unlikely Ones, to pick a random example, is as straightforward a plot coupon fantasy quest as you can ask for (and it still ends in marriage). But they’re swimming valiantly against an undertow, which is the great preponderance of young men who come of age in fantasy by questing. I’m thinking particularly of the trope of the Scullery Boy Who Would Be King, and I can reel off examples by the cartload, from Lloyd Alexander’s Taran to Robert Jordan’s Rand Al’Thor. (Scullery Girls Who Would Be Queen are so rare as to be nearly nonexistent.) Fairy tales, too, are full of these young men, scullery boys or woodcutters’ youngest sons or vagrants, and there’s even a version of the motif in The Lord of the Rings: although Aragorn is not a child, his path through the trilogy is very distinctly from undervalued outsider to King of Gondor. All of them are the protagonists of bildungsromans, of quests, and the pattern they trace inexorably has shaped and continues to shape the way we think about fantasy as a genre and what we think it can do.

I don’t want to argue against bildungsromans in fantasy—far from it. I don’t want to argue against quests, or even against scullery boys. But I want to argue for awareness of the patterns that we have inherited—the grooves in the record of the genre, if you don’t mind a pun—and for awareness that patterns are all that they are. There’s no reason that scullery boys have to turn out to be kings. There’s no reason that women’s bildungsromans have to end in marriage. There’s no reason that fantasy novels have to be quests. It’s just the pattern, and it’s always easier to follow the pattern than to disrupt it.

But you don’t have to.

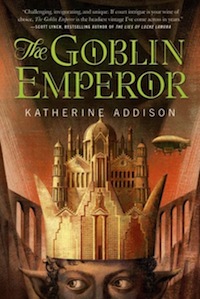

The Goblin Emperor starts where the bildungsroman of the scullery boy ends, as an unprepared young man discovers that he is now the emperor. The book turned out, in many ways, to be a methodical disassembly of the idea that becoming emperor is in any sense a victory condition, a “happily ever after.” Maia’s bildungsroman is confined to the imperial palace, and it became clear, both to him and to me, that he was as much a prisoner as a ruler: he couldn’t have gone wandering across the continent on a quest, even if there had been a quest available. He has to reach adulthood and self-knowledge in other ways, ways that are more passive and thus traditionally “feminine,” while at the same time the women around him are fighting to achieve adult identities that aren’t just “wife.”

Any bildungsroman is a quest. Where the scullery boy’s quest is to find his rightful identity as king, Maia has been forced into an identity as emperor that he feels is wrong, and his quest is to find some way of making this external identity match his interior sense of self. Along, of course, with ruling the empire, learning to negotiate the court… and, oh yes, surviving to his nineteenth birthday.

Katherine Addison is the pen name for Sarah Monette. Sarah grew up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, one of the three secret cities of the Manhattan Project, and now lives in a 108-year-old house in the Upper Midwest with a great many books, two cats, one grand piano, and one husband.Her latest novel, The Goblin Emperor, comes out from Tor in April 2014.